Coat of Arms of the Clan Buchanan - the crest, showing an arm holding a ducal cap aloft in triumph, commemorates Sir Alexander Buchanan's killing of the Duke of Clarence, Henry V's brother, at the Battle of Baugé [1421]

THE THISTLE, THE ROSE & THE LILY – HOW SCOTTISH OBSTINACY HELPED FRANCE WIN THE HUNDRED YEARS WAR…

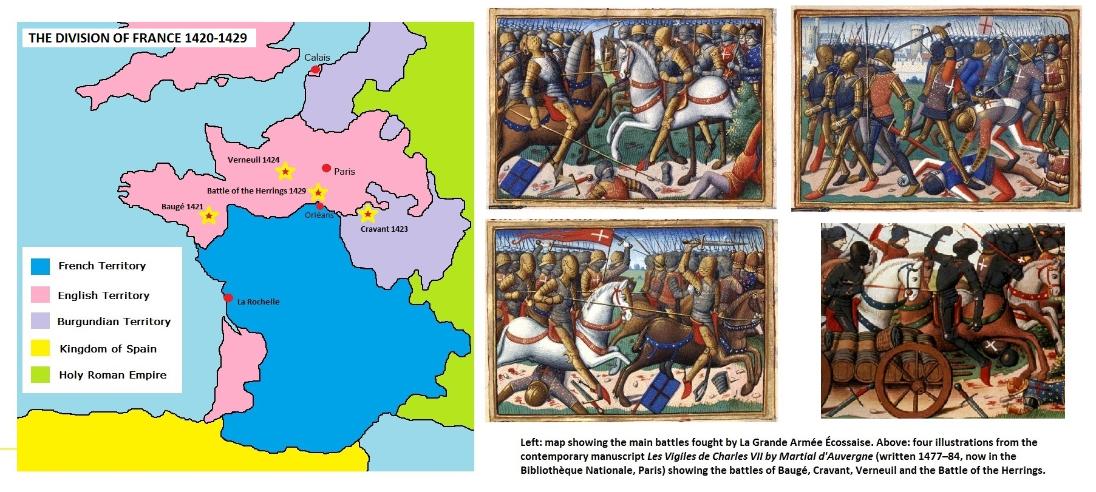

The loss of 10,000 highly trained knights and men-at-arms at the Battle of Agincourt [1415] left France at the mercy of the victorious English so, in desperation, the French turned to Scotland for help. In 1418, the Dauphin Charles (heir to the French throne) renewed the ‘Auld Alliance’ with England’s hereditary enemy in the north and 8,000 Scotsmen set sail for France.

What became known as the Grande Armée Écossaise landed at the French port of La Rochelle in October 1419 whereupon the Dauphin granted the Earl of Buchan, and the other nobles commanding the Scottish army, large estates in France as a welcoming gift. Charles also selected 100 of the best common soldiers to be his personal guard and this encouraged more Scots to seek their fortune abroad. Another 5,000 enthusiastic Caledonians arrived in 1420, which made the Grande Armée the largest independent Scottish military force ever to fight overseas, yet in theory the war was over.

The Treaty of Troyes [1420] recognised Henry V’s sovereignty over northern and western France whilst making Henry’s newborn son heir to both the English and French crowns. This treaty effectively disinherited the Dauphin but Charles was determined to use his new Scottish army to regain his crown - and Buchan’s first mission was to stop the English raids that were devastating the countryside still in French hands.

These chevauchée (literally ‘horse-rides’) were led by Henry V’s younger brother the Duke of Clarence and on Good Friday 1421, Buchan found his enemy encamped at Baugé in the Lower Loire Valley. Fortunately for the Scots, many of Clarence’s archers were away searching for plunder but, despite holding the advantage, Buchan agreed to a two day truce to celebrate Easter! Clarence should have used this delay to fortify his position and wait for his archers to return; instead, as soon as the truce was ended, the English prince led a foolhardy charge against the Scottish lines.

In a mirror image of Agincourt, Buchan’s archers made mincemeat of the English men-at-arms and during the hand-to-hand fighting that followed Clarence was killed by the Scottish knight Sir Alexander Buchanan. Ever since, in recognition of Sir Alexander’s heroic feat, the heraldic crest of the Clan Buchanan has featured a duke’s coronet being held aloft.

After Henry V died suddenly in 1422, his infant son became king of both England and France as per the Treaty of Troyes but the war continued and, in the summer of 1423, Buchan attacked England’s ally the Duchy of Burgundy. On the 31st July, at Cravant near Auxerre, Buchan’s Franco-Scottish army met an Anglo-Burgundian army led by the Earl of Salisbury.

The battlefield was divided by a river, crossed by a narrow bridge, but Salisbury ordered his men to outflank the French by fording the waist-high waters. On seeing the English advance, the French began to withdraw but the Scots refused to be disgraced by a retreat and stood their ground. Abandoned by their allies, Buchan’s men were quickly surrounded and 3,000 Scots perished in the fighting. Buchan himself was captured after being wounded in the eye but he was soon ransomed and rewarded for his pig-headed heroism by being made Constable of France.

Buchan was now commander-in-chief of all the Dauphin’s forces and on the 17th of August 1424, having been reinforced by another contingent of Scots under the Earl of Douglas, he led a huge Franco-Scottish army to relieve the besieged Castle of Ivry in Normandy. Unfortunately the fortress surrendered before Buchan arrived so the Scots turned their attention to the fortified town of Verneuil nearby. The Scots captured this bastion of English power by the simple ruse-de-guerre of pretending to be English reinforcements!

Angered by the loss of Verneuil, the Duke of Bedford, who’d replaced his brother Clarence as head of the English army, immediately marched to recover the town and what followed was the bloodiest battle of the entire Hundred Years War. Once again, the Scots refused to surrender and this time 4,000 Scotsmen were cut down where they stood. Among the dead were the Earl of Buchan, the Earl of Douglas and Sir Alexander Buchanan. Clarence had been avenged.

The destruction of the Scottish army at the Battle of Verneuil meant Orléans was the only large city in Northern France left in French hands (even Paris had fallen to the Burgundians) but it wasn’t until 1428 that the English laid siege to this vital stronghold. By this time, the few hundred survivors of the Grande Armée Écossaise had been absorbed into the main French army but their stubbornness still played a key role in deciding the outcome of the Hundred Years’ War.

In February 1429 Sir John Fastolf (the model for Shakespeare’s Falstaff) was taking supplies to the English siege-works at Orléans and, because it was Lent when everyone had to eat fish rather than meat, the 300 wagons were loaded with barrels of herring. The French, now led by the Count of Clermont, chose to attack the lumbering column in the middle of a plain which gave the English plenty of time to form their wagons into a circle and plant sharpened stakes to keep cavalry at bay.

Having missed the opportunity for an ambush, Clermont decided to use his newfangled cannon to obliterate the English wagon-fort but the impetuous Scots, eager to slit English throats, ignored his order to stand fast and attacked. Forced to stop his artillery barrage for fear of hitting his allies, Clermont ordered his cavalry to charge in support the Scots but, just like at Agincourt, Fastolf’s archers mowed them down. Yet again the Scots refused to retreat, and they died where they stood whilst the French survivors fled.

Though the ‘Battle of the Herrings’ was little more than skirmish, Clermont’s failure to prevent vital supplies reaching the English lines led to his disgrace and he gave up his command of the French army soon after. Clermont was replaced by a young girl who’d told the Dauphin of ‘a shameful defeat’ long before messengers arrived with the official news; the name of this prophetess was Joan of Arc and the rest, as they say, is history.