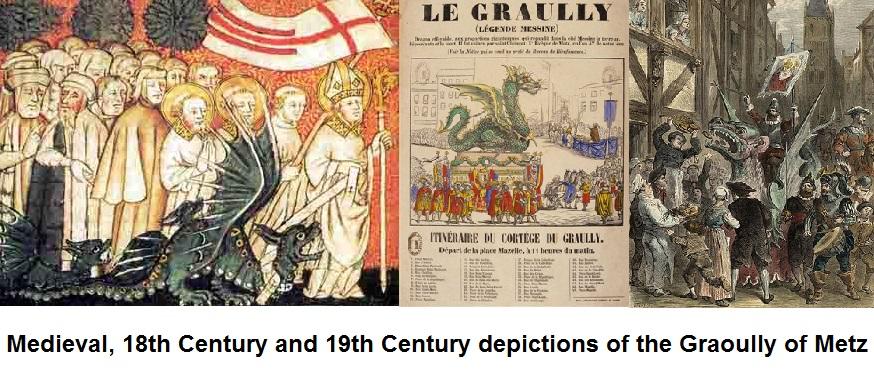

HERE BE DRAGONS – ST CLEMENT & THE GRAOULLY OF METZ

In April 1546 the French writer Francois Rabelais was visiting Metz, then a free republic within the Holy Roman Empire, when he saw a crowd of children beating a huge puppet of a dragon as it was paraded through the city. This 12 foot high marionette, which was called the ‘Graoully’, was made of canvas stuffed with hay and Rabelais was so intrigued by the ceremony he included a description of it in the Fourth Book of his epic satire ‘Gargantua & Pantagruel’:

“It was a monstrous, hideous effigy, terrifying for small children, with eyes bigger than the stomach, and a head bigger than the rest of the body, with horrific, wide jaws and lots of teeth which were made to clash by the use of cords, making terrible noises as if the dragon of St Clement was actually in Metz.”

The Fourth Book of Pantagruel contains Rabelais’ observations on religion and even in the 16th Century the ‘Whipping of the Graoully’ was a very old religious festival that dated back to at least the 10th Century. The procession supposedly commemorated St Clement's conversion of the Messines to Christianity and the story goes something like this:

Sometime during the 3rd Century AD (though some sources place these events in the 1st Century AD ) Bishop Clement travelled from Rome to Gaul in the hope of converting the pagan tribes of the Moselle Valley but when he arrived in Metz he found that the city's population were trapped in their homes by a monstrous dragon. The dragon’s lair was the city’s amphitheatre and it was guarded by a swarm of poisonous snakes with breath so toxic no living thing could approach the ancient arena.

In spite of this peril Clement offered to rid the city of both the snakes and the dragon if the people of Metz agreed to be baptised. The terrified Messines were only too happy to make such a bargain so Clement set of for the amphitheatre. The moment he set foot inside the crumbling ruin, he was attacked by the vicious reptiles but Clement made the sign of the cross and the dragon, together with its attendant snakes, were instantly calmed.

Tying his bishop’s stole around the dragon’s neck he led it to the banks of the river Seille but, not wishing to kill one of God’s creatures, he commanded the Graoully to live in place where neither men nor beasts could dwell. The dragon and snakes obediently dived into the river and were never seen again. Amazed by this miracle, the grateful Messines rushed to be baptised, though one version of the tale says that Orius, ‘king of Metz’, refused to convert until Clement had raised his daughter from the dead.

Though there’s no historical proof of Clements’ existence the story of the Graoully, like many other early medieval dragon myths, is probably an allegory for the triumph of Christianity over paganism. Equally the dragon’s strange name ‘Graoully’ is likely derived from either a medieval German word meaning ‘monstrous’ or from the old French word for ‘swarm’. Whatever the origins of the legend, the annual procession of the Graoully through Metz was very popular throughout the Medieval and Early Modern Periods and was only discontinued when the French Revolution put a stop to many similar Christian festivals.

Despite the demise of the procession, the Graoully remains a much loved symbol of Metz and this legendary dragon now appears on everything from the city’s cathedral to the badge of the local football team. The story of the Graoully even makes a useful plot device in my book The Devil’s Band! To order click here