HENRY VIII

"We are, by the sufferance of God, King of England; and the Kings of England in times past never had any superior but God"

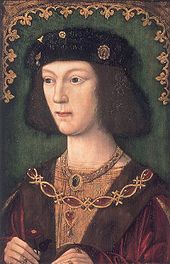

Henry VIII at his coronation, aged 18 [1509]

Henry VIII in his early twenties

Henry VIII in 1531

Henry VIII [1491-1547] was never meant to be king. In fact Henry wanted to become a priest but his elder brother Arthur, who was supposed to continue the Tudor dynasty begun by their father Henry VII, died young.

The reluctant Henry succeeded his father in 1509 and was promptly married to his brother's twenty four year old widow Catherine of Aragon. Though the marriage was political, the Tudors needed Catherine's powerful Hapsburg relatives as allies, and required a papal dispensation to repudiate the biblical prohibition on such unions, the marriage was happy... at least for the moment.

Though Henry's father had ruled England for more than twenty years, Tudor grip on power was still tenuous. Henry VIII reigned because his father had defeated and killed Richard III, the last king of the House of York, at the Battle of Bosworth [1485], but there was a Yorkist claimant to the throne still living. Richard de la Pole, the Duke of Suffolk and self styled White Rose, lived in the free city of Metz and presided over a Yorkist court in exile. Richard had the support of the French King Francis I and managed to escape all the assassination attempts organised by Henry's scheming Lord Chancellor Cardinal Wolsey.

Ever mindful of Yorkist plots and revolts, Henry decided the best form of defence was attack. He reasoned that a war to reassert his claim to the French crown and recover England's French territories, which had been lost during the Hundred Years War [1337-1453] would win the support of the rebellious English nobility but Henry VIII was no Henry V. The Tudor invasion of France in 1513 produced a minor victory at the Battle of the Spurs, the capture of the strategically unimportant city of Tournai and the crushing of France's Scottish ally at the Battle of Flodden but it did not bring Henry any closer the French throne. Instead Henry became mired in European politics which bankrupted his treasury and produced nothing in return.

To support his Hapsburg allies, Henry had to contribute to a new invasion of France by Charles Duke of Bourbon, a French rebel prince who was determined to win the throne of France for himself. In return for English and imperial gold, Bourbon agreed to restore the provinces of Gascony, Anjou and Normandy to England and cede the ancient Duchies of Burgundy, Lorraine and Flanders to the Hapsburgs but Bourbon was easily defeated and his promises came to nothing.

With the defeat of Bourbon in 1524, Henry abandoned his dreams of conquest and though there would be a new invasion of France in the 1540s the English king was becoming increasingly vexed by his queen's failure to provide him with a male heir. By 1525 it had become clear that Catherine could not bear her husband any more children but Henry could not risk a divorce as this would alienate her powerful nephew Charles V, the King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor.

Henry's only hope was an annulment of the papal dispensation that had allowed him to marry his deadbrother's wife in the first place. For years Henry employed the best theologians to find a loophole in the biblical prohibition on marrying the widows of deceased relatives and when they failed to convince pope Clement VII, who had his own problems with Hapsburgs, Henry felt he had no choice but to dissolve the entire Catholic Church in England.