NECROMANCY

PROPHESYING THE FUTURE BY RAISING THE DEAD

The Witch of Endor by Jacob van Oostsanen [1526]

Attempting to foresee the future by interrogating the shades of the dead is a practice as old as history. The classical heroes Odysseus and Aeneas visited The Underworld to converse with their deceased ancestors and the Biblical king Saul ordered the Witch of Endor to raise the spirit of the prophet Samuel in defiance of his own laws forbidding such practices.

Christianity also adopted the Judaic prohibition on necromancy (Leviticus 20:27) but despite the burnings, hangings and other dreadful punishments meted out to necromancers and witches the practice of magic continued.

Throughout the Middle Ages monarchs, princes and even popes employed mystics to help steer their ships of state through stormy waters. To give just two examples: Elizabeth I appointed the magus John Dee as her court astrologer and Catherine de Medici Queen of France regularly consulted Nostradamus.

Medieval and Renaissance necromancy was a fusion of several different magic traditions including European folklore, Eastern astrology and Jewish Kabbalah. As result, the rituals described in medieval grimoires (spellbooks) were often an eclectic process involving the fumigation of magical amulets with charmed smoke and burying them in a particular place, at a specific hour, whilst reciting a complicated spell.

Pagan necromancers usually tried to contact the spirit of a deceased prophet or ancestor but Christian theology insisted that any spirit raised by magic was inhabited by a demon trying to enter the world by subterfuge. This warning did little to discourage necromancy and magicians even began trying to contact specific demons. They also devised complex magic circles to protect themselves from the evil they conjured.

A woodcut depicting Faust protected by a magic circle

19th Century engraving of the demon Astarothwho could lead the necromancer to hidden treasure

To successfully raise a demon the necromancer also had to know the fiend's name and the magical sigil (symbolic seal) that would summon it from The Pit. To assist the magus in this, scholars of the occult produced numerous books cataloguing the different hierarchies of demons and the spells required to summon these lords, presidents and kings of Hell.

One of the most famous of these books was The Lesser Key of Solomon. This work was compiled at the end of the 16th Century from earlier manuscripts and is divided into five books. One of these, the Ars Goetia, describes no less than 72 demons and the areas of human endeavour that they were supposed to govern.

Whilst there is no evidence that any of the spells listed in the medieval grimoires succeeded in summoning the spirits of the dead, demonic or otherwise, the belief in necromancy persisted and even enjoyed a revival during the 19th Century.

Despite (or maybe because of) the huge advances in science and technology produced by the Industrial Revolution, Western Europe and the USA has seen a proliferation of paranormal investigators, esoteric societies, mediums and spiritualist churches during the last hundred and fifty years.

All of these modern necromancers claim to be able to unlock the mysteries of the universe by contacting the dead but whether they are any more successful than their medieval counterparts remains a matter for debate.

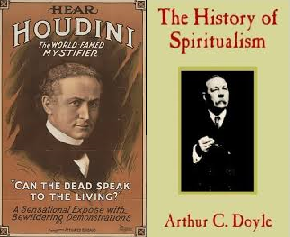

Arthur Conan Doyle and Harry Houdini took opposing views on the subject of speaking to the dead